We had been sitting across from each other for 15 minutes, and as the alcohol swam into my bloodstream, my nerves dissipated and were replaced by a desperate desire to laugh. I was 30 years old, utterly, shamelessly gay, and on my first ever date with a man. He was skinnier than his photographs, his face pointier, and his gestures unexpectedly camp. He had pretty grey eyes and he knew more than I would have imagined about cricket in the postcolonial novel. In fact, that’s all he had talked about since I arrived. He was taking my uninformed but spirited opinions very seriously.

I took long gulps of red wine and wondered what on earth I was doing. This wasn’t the plan! This wasn’t right at all! I didn’t want to sit across from some man in a pub, talking about literature and gentrification and whether the night tube was a good development. I didn’t want to know that he’d bought a new bike off Gumtree or that his parents were getting a divorce. I didn’t even want to know his name. The whole thing felt wrong – not dangerous or disturbing, just bizarre. I was queer. I liked women. What was I doing here with this earnest bearded man?

On the endless bus ride home after an embarrassingly adolescent fumble (I’m not going all the way to East London for nothing, and I was determined to see my experiment through to the end), I was too exhausted and wine-addled to read. I looked out the window and tried to account for the vast, clumsy gap between fantasy and reality.

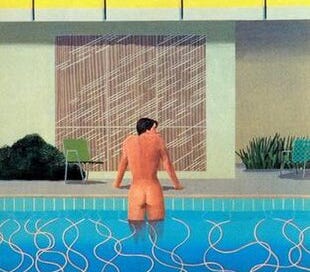

As strange as it sounds, the reason for my flirtation with heterosexuality came from reading Alan Hollinghurst, the first gay winner of the Booker prize and a pioneer of queer British writing. I’m pretty sure his first novel, The Swimming-Pool Library, changed my sexuality.

The novel follows the sexual adventures of Will, a young wealthy white gay man, as he traverses London picking up younger working class men for sex. Through a chance encounter in a public toilet, he meets his older counterpart, the forceful and lubricious Charles Nantwich, whose diaries of his colonial sexual exploits in Sudan sound suspiciously similar to Will’s adventures in 1980s London. Charles turns out to be a gay aristocrat who is imprisoned after being caught soliciting sex in the 1950s. The politician driving the attacks on gay men was Will’s grandfather, on whose wealth Will’s leisurely lifestyle of drinking, cruising and the occasional swim, relies. The connection between Charles and Will’s grandfather, proleptically concealed until the book’s final few chapters, gives Hollinghurst’s critique its sharpest sting: though homophobia was enforced by the political elite, gay men have always walked the corridors of power.

In the novel, Hollinghurst uses Charles Nantwich’s diaries of political service in Sudan to suggest that British colonial administrators saw the outposts of the empire as an opportunity to test out their queer fantasies, without fear of the reproach they might have met back home. He muses that ‘there was a tendency to treat Africa as if it were some great big public school.’ Beyond a knowing nod to public schools as dens of adolescent sexual exploration, this comparison shows how Britain’s colonial exploits and the class system back home were intricately connected – off they went, these powerful men, from Eton to Africa, having a glorious time!

Charles suggests that the presence of gay men the British Empire was not coincidence but design, saying ‘On the gay thing […] they were completely untroubled – even to the extent of having a slight preference for it in my opinion. Quite unlike all this modern nonsense about how we are security risks and what-have-you’. The remark would have resonated quite differently in the 1980s when the novel was published and when the AIDS epidemic was ravaging Britain’s gay community, though its implications are perhaps even more striking now; we’re always told that the gay-friendly present has swept away history’s homophobia, so there’s something subversive in claiming the opposite.

Despite Hollinghurst’s stinging critique of imperialism, the novel makes for uncomfortable reading. The text is saturated with images of men, with the author’s eye resting at length on the bodies of black and working-class men. Hollinghurst devotes great swathes of the novel to describing, categorising and evaluating dozens and dozens of men. At one point, the text threatens to spill over into self-parody, when the narrator waxes pornographic about different kinds of cocks. ‘O the difference of man and man. Sometimes in the showers, which only epitomised and confirmed a general feeling held elsewhere, I was amazed and enlightened by the variety of the male organ.’ The narrator’s impulse to classify also links him back to European empires and their project of naming and categorising everything, from plants to people, that they encountered in the colonies. And yet, I was left not with a sense of a world ordered by labels, but of an abundance that can’t be contained by categories.

It might seem strange for a novel so drenched in the complex histories of race and empire to have such an impact on my desires, but politics and sex mix more easily in fiction than in life, as a well-crafted sentence or striking image slips through all but the most dense and rigid of political nets. The novel is witty and erudite – it channels EM Forster and Ronald Firbank, as well as a slew of biblical and classical allusions, and has a well-tuned ear for dialogue, especially the eloquent verbal violence of the English ruling-class. The prose is lush and lyrical, it feels like a luxury good yet also stays deeply connected to the queer subcultures of cruising, clubbing and cottaging. The way the novel infiltrated my life for a few days was not just due to its content, but to its lyricism. Perhaps this is both the risk and the potential in representation.

The power of literature in other domains is well-noted, with many recent high-profile attempts to improve diversity and representation in fiction. The logic underlying these initiatives is that there is a relationship between the stories we read and how we feel about ourselves, and being invisible within high culture compounds economic or social marginalisation. Implicit in this drive for better representation is the idea that seeing oneself reflected in fiction – being able to identify with characters in novels, for example, who share our identities as women, or people of colour, or queers – could yield positive emotional effects for individuals, and even close the social disparities between groups.

Conversations often take a more abrasive tone when it comes to representations of sex. Anti-porn feminists have gone as far as to say that pornography is the ‘theory’ and rape the ‘practice’ and in doing so made some strange bedfellows of neo-conservatives who also wanted to ban pornography. The queer feminist writer, Judith Butler points out, critiques of pornography as sexist rely upon a ‘representational realism’ – essentially, a belief that seeing might be a precursor to doing. This argument tends to assume that identification runs along the same lines as identity; that we feel a kinship with fictional characters based on a shared social identity.

For me, one of the most interesting aspects of reading Hollinghurst is that there is no point of identification along racial or gender lines. There are no women in the novel at all, certainly no queer Asian ones. Yet this did little to blunt the novel’s impact on me. Reading The Swimming-Pool Library transformed London into a space of erotic possibility that simply does not exist in the same way in my every day life. Incase you were under any more exciting illusions, dykes don’t cruise for sex in the street. We sometimes fuck in club toilets, but almost never in public loos, graveyards, or parks. Yet, while reading The Swimming-Pool Library, doing so felt like a very real possibility. Its pornographic bent slipped into my psyche, just as the anti-porn feminists had warned. But with a twist.

To give you an example, I usually bike everywhere, so I am rarely in the sexy transit situations so frequent in the novel. Yet while I was reading the novel – perhaps due to its unconscious influence – I was taking the bus home from Bloomsbury to Camberwell, engrossed. As the bus snaked slowly down the Walworth Road, I realised that the young man next to me was reading over my shoulder. In the novel, the protagonist and his new conquest were entering a hotel on Russell Square, exactly where I had just left. The man beside me neither concealed nor performed the attention he was paying to the book in my hand; I tried to match his easy, detached confidence. If I got off at the next stop, would he follow me? Would we walk, silently, into the thick darkness of Burgess Park, around the concrete lake to the side that borders the Old Kent Road? With the rumble of traffic in our ears, would we be silent or swap names? Would I suck his cock? Would we fuck? Do people kiss in these situations? If I got off at the next stop, would he follow me? No! Of course, he wouldn’t. And yet, caught between the humdrum reality of the 68 bus route and Hollinghurst’s city of casual sex, for a moment, the boy and the bus glowed with possibility.

The novel saturated my interior world, as novels do, and distorted my sense of the city. It also distorted my sense of myself, as the bus anecdote suggests. This distortion was not borne out of my identification with the protagonist – a man I have almost nothing in common with – nor with his sexual conquests, who were more like sculptures than men anyway. I felt no fixed point of identification with any particular character, yet the queer lifeworld of the novel was intoxicating, capacious enough to inhabit, specific and hidden enough to retain the thrill of secrecy.

On that other bus ride home, from my first (and probably last) date with a man, I realised that the problem had been that I was trying to impersonate a straight woman, when in fact, it was the novel’s gayness that I had found so compelling. It wasn’t men that I was interested in, but the relationships between men. Casual sex between men is portrayed as thrilling and exciting, but not dangerous per se; every busy street or twilight bus stop contains the possibility of connecting across the boundaries of race or age or class. This is radically different from the experience of most women, for whom public space is the likely stage for sexual harassment. There was something thrilling about seeing the city’s streets and parks and alleyways as a space of sexual possibility, rather than of threat, even if this was an experience that was largely imaginative.

I wondered again about the novel’s charged racial politics. Critics have often pointed to the objectifying descriptions of men of colour in the novel, yet it seems clear to me that it is these descriptions that make Hollinghurst’s critique of imperialism so effective; through the writing, we are able to see and to feel that empire was tangled up with sexual desire, and are forced to question what political systems continue to impact on our desires.

Literary critic, Brenda Cooper explores the issue of the novel’s political and racialised allegiances at length. She makes use of art historian, Kobena Mercer’s work on the white gay photographer, Robert Mapplethorpe, who took highly sexualised photographs of black men. Mercer wrote two papers on Mapplethorpe’s photographs, the first damning what he viewed as a racist white male fantasy of black men as hypersexual. In the second, Mercer reflects on his own subject position as a black gay man.

In the original paper, he suggests that the viewer is constructed in Mapplethorpe’s own image: as a white man. In his re-reading years later, he revises this idea, suggesting that part of his discomfort actually comes from the fact that he felt himself in both photographer and sitter positions, as desiring and desired, objectified and objectifying.

In some senses, my own relationship to Hollinghurst’s novel is the inverse of Mercer’s; I found myself in neither position, totally outside of the novel. And yet it was exactly this sense of being outside of the novel’s world in my own life that gave entering it such a frisson. Perhaps this is the potential in representation, that we can imagine ourselves in every position, regardless of where our real lives have taken us.

But the imagination only takes us so far. I decided to return to my experiment. I downloaded Scruff – a hookup app for gay men – and made a profile. With a hoodie and cap, I passed as a pretty cute guy, though I made it clear in my description that this was something of an illusion. The messages started coming in – u free now?, u hot, u horny, wanna meet, more pics, you got more pics, u free, host? can u host? – and the ‘dick pics’ which have become such a talking point in our digital lives. It wasn’t quite the sexual utopia of Hollinghurst, but it had the same sense of endless possibility. As I stood in queues and sat in restaurants, I would surreptitiously scroll through man after man – the pleasure was less in the images or conversations, and more in the sense of sex as something hidden in plain sight – a bit like cruising.

As a dyke, it felt impossible to simply turn up at a man’s house for a hook up in the middle of the night – too forward, too risky – but in my new gay man persona, I decided to give it a try. On the 188 bus to Shad Thames, my heart raced in terrified excitement, and I forced myself to not touch my phone, which was down to 30% battery. If it died, my encounter would be over before it began. I made it to his front door and pushed the buzzer. As he let me in, I realised I didn’t know his name.

I wouldn’t find it out until an hour or so later, when he walked me back to the door and, grateful that my phone had lasted the night, I hopped into an uber. With the strange buoyant confidence that comes from stepping out of one’s regular life and into the unknown, I asked the driver if I could connect my phone to the speakers – this is the kind of thing I never do – and pressed play on 'Pink + White'.

Listening to Frank Ocean and texting my friends the story, another snippet of queer theory came back to me – Michael Foucault’s quip that the best moment of an encounter is when you put the boy in the taxi. This time, I was the boy in the taxi. It seems telling that immediately I imagined myself through my conquest’s eyes. Just as when reading Hollinghurst, I was unable to maintain the sense of a singular self; it seemed to dissolve as soon as desire entered the picture.

We take up all of the positions in a novel simultaneously as we read, so our sense of self becomes broken up, distributed in new and unexpected ways. This idea is most commonly understood as the power of empathy, but lust, empathy’s seedier underbelly, might be just as fruitful. The erotic – and the political – potential of literature may be not be found in identification but in the possibility of a break from identity altogether, in having ourselves changed in unpredictable ways that show our identities, however precious they may feel to us, to be malleable, changeable, and more easily undone than we like to think.

(Originally published on Boundless as 'Cruising Alan Hollinghurst's Contradictions' in 2018. Boundless has now folded, so I have retrieved my essay from the digital void to republish here).

as a highly nosey person i read and enjoyed this when you first published it, but this time am also really feeling the empathy and representation in novel bits.